What you think of as “reality” is mostly a hallucination—crafted by your brain, filtered for survival, and edited to keep you sane. The world feels complete because your mind is good at hiding the gaps. But if you step back and look at what we actually see, hear, touch, smell, and know, you realize something unnerving:

You’re only accessing a tiny slice of what exists. The rest is filtered out.

The Spectrum We Can’t See

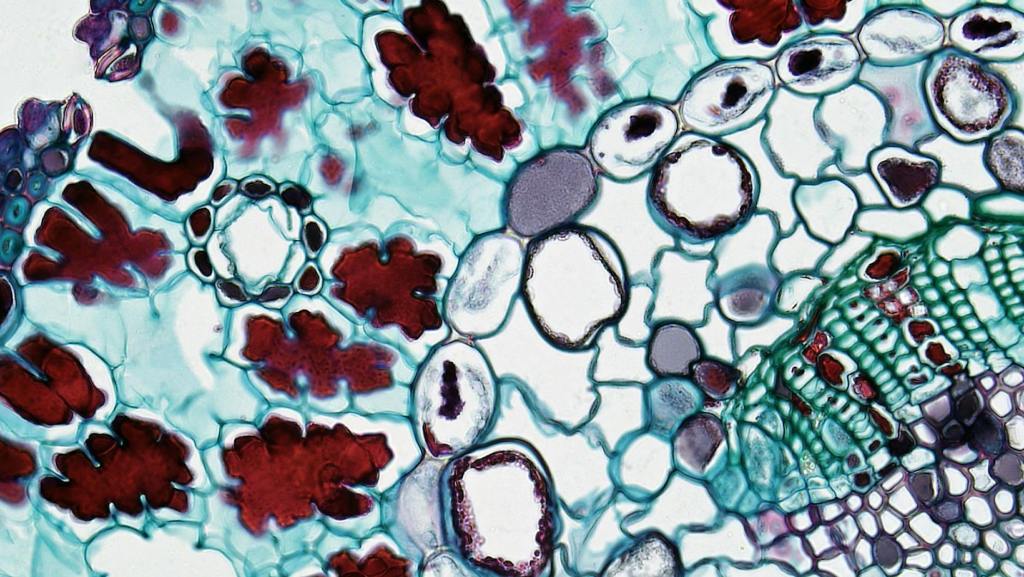

Let’s start with light. The visible spectrum—the colors your eyes can detect—makes up less than 0.0001% of the electromagnetic spectrum. That’s not a typo. Everything you’ve ever seen with your eyes, from sunsets to supernovas, is confined to this razor-thin band between about 400 and 700 nanometers in wavelength.

Above it? Ultraviolet, X-rays, gamma rays. Below it? Infrared, microwaves, radio waves. All real. All around you. All invisible.

Bees can see ultraviolet patterns on flowers that we can’t. Snakes can detect infrared heat signatures. Birds use magnetic fields to navigate, something humans can’t sense at all. Reality, it turns out, depends on who’s looking—and with what.

Hearing, Touch, and Smell: More Limits

Your hearing range? Around 20 Hz to 20,000 Hz. Elephants communicate with infrasound—below human hearing. Dolphins and bats use ultrasound—above it. Sound exists far beyond our perception. The world is full of frequencies we can’t hear.

Your sense of touch is mostly pressure, temperature, and vibration. You don’t feel magnetic fields. You don’t feel ionizing radiation. You don’t feel atoms moving, despite the fact that the molecules in your skin are vibrating constantly.

Smell? Extremely limited. Dogs have up to 300 million olfactory receptors. Humans? Around 5 million. Entire layers of scent-based communication are invisible to us.

So again, what we sense is just a slice. Not reality—it’s your reality.

Your Brain Hides the Rest—On Purpose

Here’s where it gets wild: your brain isn’t even using all the sensory data you do collect.

There are over 11 million bits of sensory information entering your brain every second. You’re only consciously aware of about 50 bits. That’s 0.0000045% of the total input. The rest is ignored, compressed, or rerouted.

Your brain’s job is not to show you the truth. Its job is to build a usable model of the world—one good enough to keep you alive. Evolution favors efficiency, not accuracy. If you had to process all the raw data, you’d be paralyzed.

Instead, your mind generates a simplified simulation based on prediction, memory, and attention. What you call “now” is not live footage—it’s an edited feed.

Vision: A Construct, Not a Camera

Vision feels real, but it’s largely synthetic. Your eyes don’t record a perfect image—they gather fragmented light patterns. The brain stitches those fragments together, fills in the blind spot, guesses where shadows should be, and pretends the world is sharp and complete.

Even color isn’t real in a physical sense. Objects don’t have color—they reflect wavelengths. Your brain assigns color to those wavelengths using internal rules. That’s why some animals see colors we don’t. And it’s why the color “magenta” doesn’t exist on the light spectrum—it’s a mental invention.

What you’re seeing isn’t the world—it’s the brain’s best guess of what the world probably looks like.

You Don’t Perceive Time As It Happens

We also don’t experience time in real time. Neuroscience shows your brain delays conscious perception by about 200 milliseconds to synchronize sensory input. That doesn’t sound like much, but it means your awareness is always slightly in the past.

During that delay, your brain aligns images, sounds, and motion—smoothing out reality like a movie editor matching frames. The result is a seamless flow, even though what’s really happening is fragmented and chaotic.

When you catch a baseball, dodge a punch, or speak fluently, you’re not reacting to the moment—you’re predicting it. The brain uses past experience and rapid subconscious processing to anticipate what’s coming. Your experience of the “present” is a delayed reconstruction.

Attention: A Spotlight on a Dark Stage

You might think you’re aware of everything in your field of view—but you’re not. Most of what you “see” is just a blurry background. Your brain creates the illusion of a detailed world by painting in what it assumes is there.

In experiments, researchers have made massive changes to visual scenes while participants looked straight at them—switching people, changing objects—and people didn’t notice. It’s called change blindness, and it reveals how little of the world you actually monitor.

Your attention is a narrow spotlight. Everything else? Ignored, blurred, or filled in by assumption. And that’s by design. Awareness is expensive—your brain saves power by focusing only on what it thinks matters.

Memory: Fabricated, Not Recorded

Even memory—our supposed access to the past—isn’t trustworthy. You don’t store memories like video files. Each time you recall something, you reconstruct it from scratch, mixing in current beliefs and feelings. Every memory is rewritten, which means every memory is a bit of a lie.

What’s worse? Your brain can generate false memories with ease. A suggestion, a photo, a single word can implant entire fake recollections that feel completely real. So not only do you see little of reality in the present—you also misremember what little you did see.

The Filter Is the Point

So why does your brain limit you so much?

Because unfiltered reality would destroy you. Imagine being aware of every photon, every vibration, every smell, every magnetic shift. You wouldn’t be enlightened—you’d be overwhelmed.

The brain works like a compression algorithm. It takes the chaos of the universe and encodes it into a functional experience: color, shape, sound, meaning. It doesn’t show you everything. It shows you what’s useful.

And in that sense, your perception is not designed for truth. It’s designed for survival.

The Big Question

If you’re only seeing a sliver of reality—what’s in the rest?

Is it just deeper physics? Or something stranger—dimensions, consciousness fields, alien intelligences living in vibrational spectra we can’t detect? We don’t know. But the fact remains:

You live in a hallucination tuned for survival. Not for truth. Not for beauty. And definitely not for completeness.

And that realization is either terrifying—or freeing.