The idea of replacing a failing organ with a lab-made version has long been a goal in medicine. In recent years, the development of artificial organs—especially through 3D bioprinting—has moved from science fiction to scientific reality. While fully functional printed hearts aren’t yet available for transplant, researchers are making rapid progress toward that future.

Traditional organ transplants face many limitations. There aren’t enough donor organs to meet demand, and patients must take lifelong immunosuppressants to avoid rejection. Artificial organs aim to solve both problems by creating compatible, lab-grown tissues from a patient’s own cells.

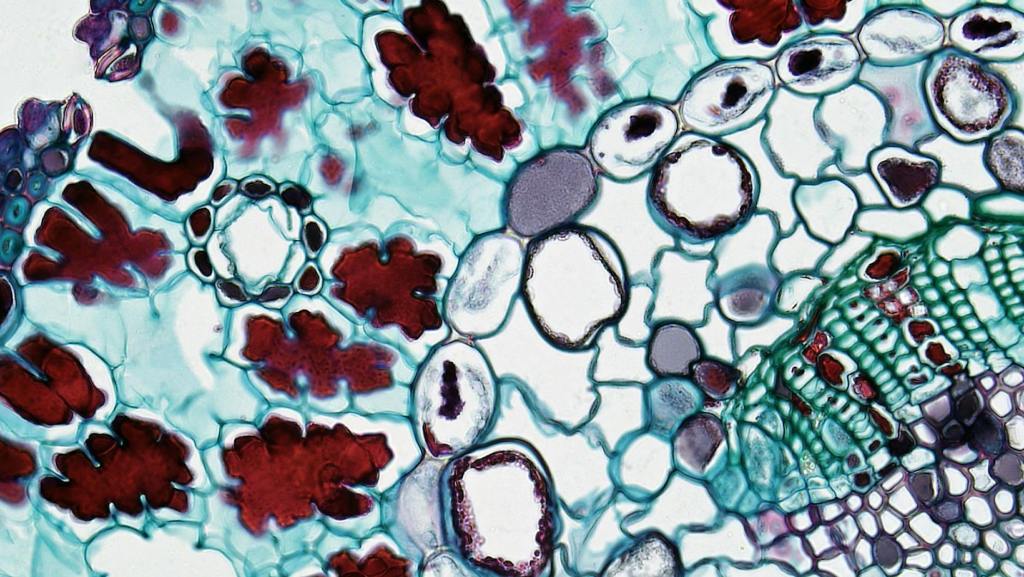

Bioprinting uses modified 3D printers to deposit layers of living cells, called bioink, in specific patterns. These cells can form tissues that mimic the structure and function of real organs. The printer builds the tissue layer by layer, incorporating blood vessels and support structures as it goes. Once printed, the tissue is placed in a bioreactor to mature.

Researchers have already created simple structures like skin, cartilage, and segments of blood vessels. More complex tissues—such as heart patches and miniature liver models—are also being tested. These constructs can’t yet replace full organs, but they are used in drug testing, disease modeling, and regenerative therapies.

The heart poses a particular challenge. It must beat continuously, respond to electrical signals, and withstand high pressure. In 2019, scientists successfully printed a tiny heart using human cells. Although it was too small and weak to function in the body, it demonstrated the ability to reproduce the organ’s basic structure, including chambers and vessels.

One major hurdle is vascularization. Without a blood supply, printed tissues can’t survive beyond a few millimeters in thickness. Scientists are working on printing networks of capillaries and using growth factors to encourage blood vessel development. Another challenge is integrating artificial organs with the body’s own systems—nerves, immune response, and cellular signaling all must align.

In parallel, engineers are developing fully synthetic organs like the total artificial heart, which uses mechanical pumps to replace heart function. These devices have kept patients alive for months or years, but they aren’t permanent solutions. Combining the mechanical reliability of synthetic organs with the biological compatibility of printed tissues may offer the best of both worlds.

Regulatory and ethical questions also come into play. How should lab-grown organs be tested and approved? What happens if the cells mutate or fail after implantation? These questions will need careful answers before widespread use.

Still, the long-term vision is compelling: printing replacement organs on demand, tailored to each patient’s biology. No waiting lists, no immune rejection, and potentially, no more deaths from organ failure. While we’re not there yet, each year brings us closer to printing hearts—not as models, but as lifesaving solutions.